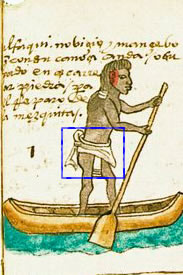

Máxtlatl (loincloth)

For over three thousand years, from the Middle Preclassic period to the Spanish conquest, quintessential male garment was worn in each of the successive Mesoamerican civilizations, with only exception (see below). The loincloth was a continuous strip of material that covered the genitals by passing between the legs and tying at the waist; in some styles the ends of the garment hung down in front and back of the body.Middle Preclassic period evidence of the garment appears both in the highlands, on clay figurines at the Valley of Mexico site of Tlatilco, and along the slow moving rivers of the Gulf Coast.

The Olmec rulers that are depicted there on sculptures wear the longer type of loincloth, supported by a wide belt, whereas altar-supported dwarfs are shown in short, apron-like genital covering held in place by narrow cords

Tilmatli (capes)

From the Middle Preclassic to the time of the Spanish contact, cloaks served as pre-hispanic Mexico´s premiere status garments. These mantles consisted of a squire or rectangle of cloth that was tied around the neck and hung down to anywhere between waist and ankle. Clay figures from the Middle Preclassic period show a waist length capes as do the lowland rules who appear on Olmec sculptures. The Classic period Maya are depicted in a variety of capes of varying lengths; the shorter versions seem more prominent.

Feathered capes appear in the Early Postclassic archaeological record, at both Tula and Chichén Itzá. Among the Aztec, the cloak – tilmatli in Nahuatl – was the prestigious, status-denoting male garment whose fiber, decoration and length were all reported by the Spanish friar Diego Durán to have been tightly controlled by strict laws. Supposedly, only the Aztec ruling class was allowed full-length, richly decorated cotton capes. However, modern day research suggests the colonial reports of such stringent regulations reflect a post-conquest, nostalgic creed rather than a pre-Hispanic, rigorously enforced reality.

Hip-cloth

This garment, always worn in conjunction with the loincloth, was a square or rectangular textile that was folded and secured at the waist. If first appears in the archaeological record in the Olmec heartland, at Tres Zapotes, the large hip-cloths in the later, Classic period, are depicted by Mayans in a variety of shapes, either folded into triangular form and tied at the waist so as to cover the buttocks, or worn over the loincloth as a frontal apron, or wrapped around the waist. At Teotihuacan, male figurines often are depicted wearing short hip-cloths and loincloths of the same length. The hip-cloths of the Toltec Lowland Maya sometimes were worn as frontal aprons; the Aztec and Lowland Maya of the Late Postclassic are also depicted in triangular hip-cloths.

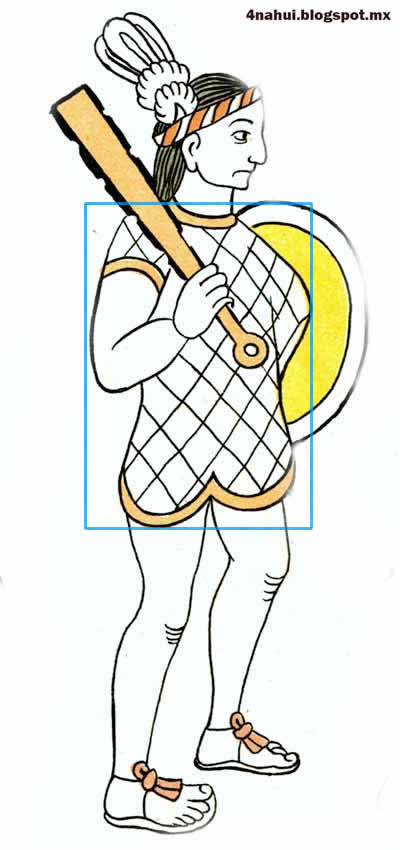

Xicolli (jacket)

It was a short, sleeveless jacket whose diagnostic is a hem area that displays some form of elaboration, often a fringe. This garment was an important ritual costume in highland central Mexico from Middle Preclassic period Tlatilco times through the Classic period at Teotihuacan and up to the Spanish colonial era. In sharp contrast, in the tropical lowlands both the Classic and Early Postclassic Lowland Maya wore the sleeveless jacket only as military attire.

Cueitl (kilt)

These special-purpose garments were reserved for deities, rules, and priests. Depictions of short kilts made of elongated jade beads strung in a diamond pattern were worn by the classic-period Mayan nobles, whereas early-postclassic Toltec Lowland Maya priests are depicted in long, straight, decorated skirts. In the Late Postclassic analogous long skirts appear in the central Mexican Borgia Group pictorials, whereas Aztec and Lowland Maya pictorials depict short kilts being worn in ritual contexts.

Ichcahuipilli (padded armor)

This protective costume was a sleeveless, thickly-padded tunic, stuffed with raw cotton and encased either by reeds, animal hide or quilted cloth. No doubt the armor was worn by warriors of all cultural groups and classes from the Classic period on, thus serving as Mesoamerican basic martial attire. Indeed, the heavily-quilted cotton armor was so effective that the Spanish conquistadors quickly adopted it.

Tlahuiztli (bodysuit)

This garment type, which completely encased the trunk and limbs, appears first at Tlatilco, worn by shamen. Subsequently, Teotihuacan males are depicted on murals dressed as jaguars carrying shields and staffs.

Similar body suits were also worn by the Classic period Maya. The Aztecs, too, had jaguar suits but theirs were made of feathers, came in four colors, and served as but one of 13 different martial styles; padded armor was worn under all of these feathered warrior costumes.

Ballgame Attire

This category includes a variety of special-purpose clothing, ranging from padded gloves to protective head and body garments that were worn by ballplayers who took part in the deadly-serious Mesoamerican game. From the Middle Proclassic period up to Spanish contact, the ballgame was consistently played and its participants, of necessity, donned a variety of protective clothing. Of special interest are the “jockey shorts” worn by the Middle Preclassic Olmec ruler depicted on Monument 34 at the site of San Lorenzo, Veracruz. This same type of hip padding was still being worn at the time of Spanish contact, as is evident in Weiditz` drawing of an animated Tlaxcalan ballplayer at the court of Charles V of Spain.

Xiuhuitzolli (elite headgear)

Throughout Mesoamerican history, members of the elite donned distinctive headgear that set them apart. Tlatilco shamen are depicted in impressive masks; helmet-wearing Olmec rules were commemorated on colossal heads; Teotihuacanos wore wide-frame headdresses bordered by exotic and expensive quetzal feathers; Classic period Maya rulers were adorned in magnificent, towering headdresses that sometimes included symbols representing their name; subsequent Toltec-Lowland Maya elite continued the use of sweeping quetzal-feather hair ornaments; Aztec nobility regularly wore the xiuhuitzolli, the royal turquoise diadem.

The original post can be read on this wonderful blog Nahui Cultura Mesoamericana.

Comments on Facebook

Comments

No Comments to “Prehispanic Male Dress”