Mesoamerican climate – never extreme and with long periods of pleasant temperatures – played an important role in shaping the region’s architecture and household furnishings.

Since building methods had barely moved on beyond ‘post-and-beam’ techniques (vertical columns or posts and horizontal beams or lintels), common people’s houses tended to be small, simple, one-room units with no windows and one entrance that provided the only source of daylight – the doorway being usually covered with a mat or a curtain with a little bell attached to hear if someone was coming in.

The houses of nobles and official and public buildings were more solid, larger and with more rooms. Temples built on the top of pyramids were small too, windowless and with minimal furniture.

Even so, both palace and farmer’s hut were perfectly fit for their purpose, since any house was almost entirely used for sleeping in and for protection from the elements; and temples serving merely for housing men and gods.

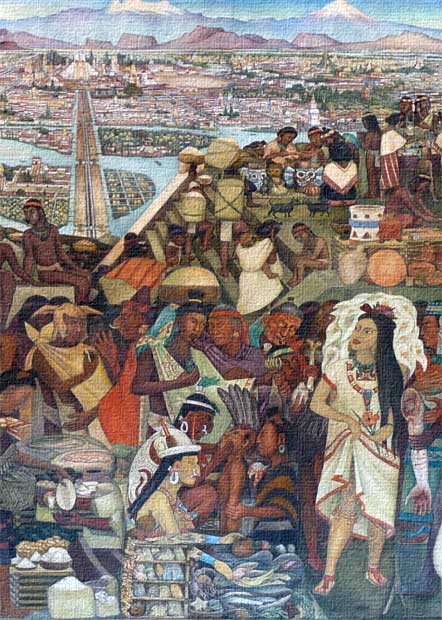

Mild temperatures encouraged people to spend most of the day outdoors, either – at home – surrounded by vegetation or in the great temple courtyard where religious ceremonies took place.

Many of the daily activities that today take place indoors were carried out in the open air, such as washing the body, cooking, grinding, peeling, weaving, looking after domestic animals, etc.

The local environment provided all the materials for making domestic furniture: clay to make washtubs, various woods, leaves and vegetable fibers, especially Tule (in Maya called zibake, in Nahuatl tollin) – a species of bulrush reed whose spongy leaves, when woven together, form springy, comfortable surfaces that feel fresh in summer and warm in winter.

The famous petate – reed mat of varying sizes – was woven from Tule and used for sleeping or sitting on. Cured animal skins – jaguar, puma, bear, wolf, coyote, and deer – were also used, though less often, as seat covers.

Indigenous households were directly affected by (good) climate, easily available local materials and the physical size of the local population. As a result furniture was frugal, light, and easily transportable and all at floor level – tables and chairs were barely more than a handspun above the ground.

The early Mesoamericans had been of nomadic origin, sleeping in the open or in caves, their only possessions being the animal skins that they slept on and covered their bodies with.

Though a very late example, we get a glimpse of this lifestyle from the Codex Quinatzin: a cave is shown in which a mother and father, wearing animal skins, cook a rabbit while the baby Quinatzin – future lord of the Acolhua – sleeps in a cradle. It isn’t until the Early Preclassic period (1500 to 600 BCE) that the first remains of woven mats are found.

Pre-Hispanic furniture, in summary, consisted essentially of beds, cradles, wash bowls, benches, chairs, storage boxes, tables, table cloths, rugs, curtains and room dividing screens.

The one universal piece of furniture to be found in every house was the bed – a mat, petatl (petate in Mexican Spanish), roughly measuring 1.35 by 1.9 meters, sometimes covered with rugs of varying weight and padded with feathers or rabbit fur, and interwoven with a variety of colors and designs.

As is the custom today in the countryside, the mat was probably shaken, rolled up and stood against the wall during the day to avoid it absorbing the cold and moisture from the ground, which was generally flattened earth or possibly stucco or flagstones in wealthier homes.

It’s worth noting that in the Maya region petates may have been placed on low wooden frames, may well also have been in use; being of perishable material these haven’t survived, though there are references to them in the early colonial era.

One, called chitatli, was used by the Chichimec’s and is still made today by a few indigenous communities. It consists of two poles bent and tied in an oval shape, covered with a net of maguey fiber and joined to form a small basket. The other is the rectangular wooden cradle with a double handle made of curved poles for carrying: inside would be placed a mat and cloths to protect the new-born.

Whilst its possible adults made use of these too, most grown-ups washed at the side of the lake or river, or used the nearest steam bath.

In popular use were small mats, commonly measuring around 80 x 110 cm, used (still today) as simple seats for resting, conversing, carrying out every-day tasks such as weaving, grinding, preparing vegetables etc. Some indigenous people today still carry these light supports rolled up under the arm, for sitting on in church, market place, town square, or for sleeping on when travelling.

Seats above floor level were small benches made of hollowed out logs of wood, often carved in the shape of an animal such as a badger, whose head and tail could serve as handles.

Elders and lords commonly sat on wooden benches with four legs. Other light and comfortable chairs were icpalli, woven from bulrush reed and used by men from all social classes. It was usual for men to sit on small benches and for women to sit modestly on mats.

Backless benches for lords (and deities!) reached high levels of luxury and refinement. One of the most elaborate pre-Hispanic benches ever recorded is that found on a stucco relief at Palenque: now disappeared, but known of thanks to a drawing made by Jean-Frédéric Waldeck [in the 1830s].

It is a throne, possibly carved from wood, with the seat in the center, covered with a soft and luxurious cushion, the arms and legs shaped like jaguars’ limbs (the arms in the form of jaguars’ heads).

In the Postclassic period [shortly before the arrival of the Spanish] wooden benches with four crenelated legs [indented like the parapets of a castle battlement], painted or lacquered and at times incrusted with decorative materials, were common in the Central Valley of Mexico and the Oaxaca region.

The rising sun god, Tonatiuh in the Codex Borgia can be seen sitting on one of these elaborate benches, and Xochipilli, patron god of nobles, rests atop a similar (stone) bench in the well-known sculpture of the deity in the Mexica Hall of Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology.

Lordly chairs with backrests, with time the low bench evolved into the tepotzoicpalli or chair with backrest (sometimes upright, sometimes angled), providing more comfort to the incumbent ruler. Examples abound from the Maya region, Oaxaca and the Central Valley. Mexica lords rested on such seats, woven with reed and frequently covered with fine animal skins.

Often, whichever type of chair was used, indigenous men would arrange themselves with their feet above the seat, knees pointing skywards or legs crossed, without losing their dignity or noble bearing. In his Primeros Memoriales Fray Bernardino de Sahagún shows a sequence of Mexica rulers; the first three, before achieving independence, are depicted sitting on icpalli; from Itzcóatl onwards they rest on tepotzoicpalli, as they are now autonomous rulers.

It’s worth nothing in passing that Aztec codices, dating from the colonial period, reveal the increasing intrusion of European art: perspective, shade, changes of proportion, and decorative Renaissance styles, as for example in the Codex Azcatitlan.

For chests the Aztecs made boxes out of wood and leather for storing family possessions. The most common were petlacalli (‘reed mat houses’), with lids, in which were kept family valuables, jewels, work tools, clothes, and relics and possibly even documents.

One of the rare instances in which the inside of a 16th century (Aztec) house is depicted can be found in the Florentine Codex. The artist captures the moment in which thieves, having used witchcraft to paralyze the occupants (seen lying on reed mats), flee loaded with petacas – the Mexican Spanish word for family chests.

Tables and screens. Pre-Hispanic families commonly gathered together to eat around the fire in the open air or in a room or covered space separate from the sleeping area. Seated on low benches or on the ground, they ate their meals with maize tortillas taken from a small basket.

On occasions the men would spread out a mat on the ground which served as a table. (Nobles used a more elaborate procedure at meal times, as noted by the Spaniard Bernal Díaz de Castillo, including the use of screens to shield them from the heat of the fire and from the gaze of servants…)

Though not mentioned by the Spanish chronicler, the dining room, bedroom and reception halls of the last Mexica ruler were luxurious – walls adorned with exquisite paintings, floors carpeted with mats and skin rugs, richly decorated chairs and benches, chests, baskets, large lacquer-painted gourds, weavings trimmed with fine feathers and other delicate adornments.

All these and more combined to render the governor’s household a comfortable and beautiful place to live, whether as a family home, when receiving foreign ambassadors, or attending to the affairs of state.

Reference: The post, compiled by Andres Michel Amezcua, is a condensed version of a chapter entitled El Mueble Prehispánico (‘Pre-Hispanic Furniture’) by Aguilera, from her book Vol. I published by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico City.

The original post. and many more fascinating articles, can be read on Andres Michel Amezcua’s Facebook page Andres Michel Amezcua (Quezaltcoalt).

Comments on Facebook

Comments

No Comments to “Aztec Furniture”