In ‘The Rise of the Aztecs Part VII’, we left Nezahualcoyotl enjoying his life in Tenochtitlan, but missing his beautiful Texcoco; and probably, his royal status as well.

Yet, this young man had evidently learned from the mistakes of his father. To try to mobilize his former Acolhua people and his newly acquired allies from the Highlands prematurely was not the wise thing to do, as it might have led to another defeat. He needed to have Tezozomoc, the old Tepanec Emperor, dead first. He needed to see how his successor will deal with too-huge-of-an-empire he’d receive. Then he may act, accordingly.

So he had curbed his impatience and waited, spending his time studying poetry, history and engineering. And touring his former Acolhua lands from time to time. Just a tourist, really. He did nothing that might have aroused the Tepanec suspicion. He was just a harmless noblemen succumbing to the spells of nostalgia from time to time. If he talked to prominent people of his former lands, if he made them arrive to all sorts of conclusions, if he offered on altars of any of the gods, praying for the imminent death of the Tepanec ruler, he did this privately and with no fuss.

In the meanwhile, his friend Chimalpopoca, the third Aztec emperor, felt differently. This young man had ascended the throne in 1417, while being only a boy of ten so years old, upon the death of his father, the Second Aztec Emperor, Huitzilihuitl. Why he had been the one to inherit the throne, no one knows. There were better-fitting candidates among the Second Emperor’s brothers, or even his sons. Tlacaelel, for one, was a few years older, and as legitimate, although sired by Huitzilihuitl’s less exalted wife. Chimalpopoca’s mother was impeccably noble and very well connected, being one of Tezozomoc’s favorite daughters. Maybe this was the reason why Tenochtitlan’s council of four districts decided to put Chimalpopoca on the throne. They might have wished to seek a favor with the old horror of the Tepanec ruler (or maybe the ambitious mother was the one to push in this direction. Like all women in history, her way to reach a real power was limited to the possibility of ruling through her underage child).

Chimalpopoca’s mother was impeccably noble and very well connected, being one of Tezozomoc’s favorite daughters. Maybe this was the reason why Tenochtitlan’s council of four districts decided to put Chimalpopoca on the throne. They might have wished to seek a favor with the old horror of the Tepanec ruler (or maybe the ambitious mother was the one to push in this direction. Like all women in history, her way to reach a real power was limited to the possibility of ruling through her underage child).

For this or that reason, Tenochtitlan’s council of four districts crowned Chimalpopoca with the special diadem, anointing him with divine ointment, and placing proper insignia of a shield and a sword in his hands.

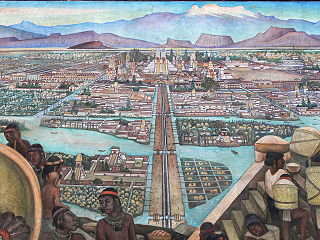

Pleased with the fact that Tenochtitlan was ruled by his progeny, Tezozomoc, through the ten years of Chimalpopoca’s reign, demanded less and less tribute, reducing it to a mere token. Many favors were granted to the island-city, such as the permission to build the aqueduct, using the springs of the mainland. And, although the water construction broke often, the relationship between the Tepanecs and the Aztecs remained affable enough.

And then, in 1427, Tezozomoc had died – a very old, very contented man, leaving his invincible empire encompassing all the lands around Lake Texcoco, and far beyond it. There was no point in trying to enlarge it any further, so he had left his throne to one of his numerous sons, a reasonable, quiet, able man.

Yet, one of his other sons, ambitious Maxtla, was not happy with his father’s choice of successor. Being sent to rule the province of Coyoacan, Maxtla didn’t seem to take it well, thinking that the throne of Azcapotzalco had suited his talents better. Only a few months into his reign, the new ruler of the Tepanec Empire had died, probably due to poisoning, and the ambitious Maxtla had taken his place.

Yet, the actions of the new Tepanec Emperor were strange. Maxtla did not rush to change the policies, conquer more lands, or make new laws. Instead he busied himself changing the governments of his tributaries and subjected lands. Successful in disposing of his own brother, he proceeded to commence a few similar projects at once.

First he tried to assassinate Nezahualcoyotl, who had managed to evade death by fleeing back into the Highlands. Unabashed, Maxtla had sent other killers to assassinate the ruler of Tlatelolco, a sister city of Tenochtitlan, situated on a nearby island and governed by another of Tezozomoc’s progeny. This time he was successful and Tlacateotl, ruler of Tlatelolco, had died under mysterious circumstances.

Encouraged by the neatness and easiness of his international policies, Maxtla decided to drive his point home further by trying to murder Chimalpopoca himself, who had previously, very openly and unashamedly, sided with Maxtla’s brother, the Tepanec lawful ruler, angering the ambitious new Emperoro beyond any reason. This time it was personal, so Maxtla had made a special effort. Various sources are debating the possible ways of Chimalpopoca’s death, but most agree that the Third Emperor of Tenochtitlan was murdered in his sleep by a bunch of skilled killers that penetrated the Palace under the cover of the night. He was around the age of twenty by this time and not a bad ruler, his political mistakes notwithstanding.

Tenochtitlan was in turmoil, but if Maxtla had counted on the hated tributaries to huddle on their island, subdued and cowed, his calculations were wrong.

In the next post, The Rise of the Aztecs Part IX, Itzcoatl, we’ll see what happened when the Aztecs were pushed too far.

An excerpt from “Currents of War”

The old leader’s grin matched that of his friend.

“My nephew is a law unto himself. But I hope they have more warriors like him.”

“Oh, please,” said Itzcoatl, then fell silent as the slaves brought in plates with refreshments, and two more flasks of octli. “Come to think of it, your nephew can be useful in more ways than just leading warriors and killing useless advisers,” he muttered, almost to himself.

Something in the former Warlord’s voice startled Tlacaelel, and he concentrated, trying to read through the dark, closed up face of his superior.

“What ways?” asked the Tepanec suspiciously, obviously as alerted.

“He can rid us of some people who are rapidly becoming a nuisance.”

“No!” called the old leader sharply. His pipe made a screeching sound, banging against the side of the table. “He is not to be involved in any of this.”

Itzcoatl looked up, unperturbed. “Why not?”

“There are twenty reasons and more, and I won’t go into any of them.” The Tepanec’s voice rose. “We are not ready for that move either, and when we are, my nephew is to be left out of it.”

“The wild beast has a mind of his own, you know. And a great will into the bargain.” Itzcoatl’s eyes glimmered, the way they always did when he was pleased with himself for having thought of a way to solve his problems. After so many summers, fighting under this man’s command, Tlacaelel had learned to read his moods as if they were written on a bark paper. “You tried to keep him away from the Palace’s troubles seven summers ago, Old Friend, and he just pushed himself more forcefully into the middle of the maelstrom. He is a law unto himself, indeed, and a priceless asset, if used correctly.” A shrug. “And anyway, he never has kept away from our politics.”

“He gets involved when his Acolhua friend is involved. But this time, the Texcocan has nothing to do with it.”

Itzcoatl’s lips were pressed thinly, his grin – a mirthless affair.

“He guards the interests of more than one highborn Acolhua. The Emperor’s Chief Wife is involved in this, even if not directly.”

Tlacaelel watched the old weathered face of their host twisting as though the man had eaten something incredibly bitter.

“Leave my nephew out of it,” he repeated stonily. “You can use his warriors’ skills all you like, but don’t make him cause any more trouble in the Palace. What happened seven summers ago was more than enough.” He picked up his pipe, concentrating on the beautifully decorated wood, running his fingers along the carvings, deep in thought. The Highlander must have made this thing for his uncle, reflected Tlacaelel, recognizing the patterns.

“It may be too soon to do the deed,” he said finally. “We should wait and see what happens in Azcapotzalco, what their new Emperor is up to.”

Comments on Facebook

Comments

No Comments to “The Rise of the Aztecs, Part VIII, Chimalpopoca, the Third Emperor of Tenochtitlan”