The magnificent mound of Cahokia, the largest man-made earthwork in North America, is towering over the surrounding landscape of the beautiful Missouri River and multitude of other man-made mounds, over 100 feet high and nearly 1000 feet long, massive, multi-terraced, imposing, humbling. It must have been puzzling many generations of people who lived in the vicinity after the builders of this particular earthwork were gone. Or maybe their descendants remained around after the great urban center dissolved, remembering their glorious ancestors, passing on stories about them.

Today, we cannot know who these people were exactly, basing even most educated assumptions on archaeology alone. According to various findings, from mass graves of what might have been sacrificial offerings to an important person who had passed away – wives? servants? – to an amazing diversity of valuables and quality goods buried in the earthworks, to the remnants of workshops and obvious signs of large urban congregation, we can safely assume that the original residents of this region might have had an hierarchical society, with this or that division of classes.

Unfortunately, in the autumn of 1492, several ships from the other side of the ocean appeared on this continent’s horizon, to affect its live and inhabitants tragically and irreversibly. Whoever lived at this time along the Mississippi River’s valleys was to face the invasion of the Spaniards at the early part of the 16th century, the invasion that failed miserably after three years of rampage and death, with its leading general De Soto dying ignobly and the surviving among his followers fleeing without looking back.

Sadly, this seemed to be a pyrrhic victory, as according to these same fleeing Spaniards’ accounts, the local peoples paid too heavy of a price, with too many cities and fortified towns left in ruins behind, whole nations burying the best of their populations, the rest left to starve, with probably the classic European diseases the Spaniards had brought completing the destruction.

Over 150 years later, the French who had sailed along the Mississippi River in the late 17th century, had found completely changed demographics that fit neither the archaeology of the region nor some of their contemporary living people’s social structures, with relatively small or midsize towns and villages displaying hierarchy of classes fitting larger and more urban societies.

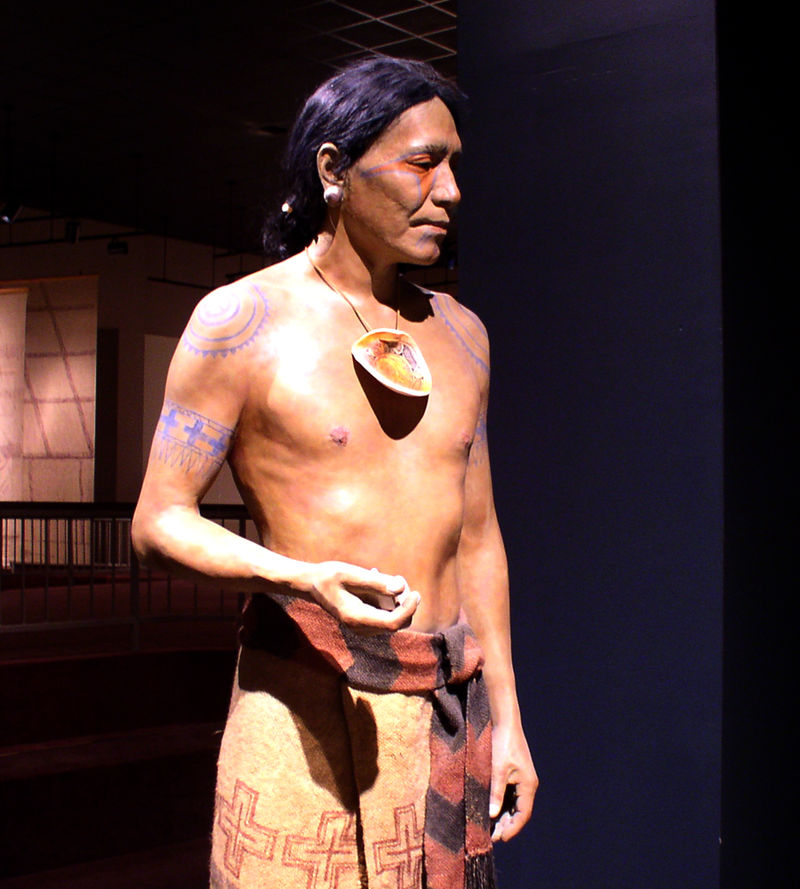

Thus, today we have Natchez People (with several others such as Tunica and Taensa) to base our understanding of the probable lives their glorious ancestors, the famous Mississippians, the builders of the more prominent among the North American earthworks, might have been leading.

At the time of the French contact, the end of the 17th century and the first part of the 18th, the Natchez were reported to occupy the Lower Mississippi Valley and its surroundings, or what we know today as Louisiana, possibly having migrated there earlier for several reasons, De Soto’s invasion of nearly two centuries earlier being one of the probabilities. De Soto’s journals do not mention the names of the powerful kingdoms he had invaded – one can assume that the conquistadors’ goals did not include proper introductions – however many reputable researchers assume that the Natchez were among those who had encountered and repelled De Soto in 1542 (Quigualtamqui polity being the “main suspect.”)

The reports on the Natchez People and their social organization and cultural life from the 18th century French are surprisingly well-detailed, and abound. From Charlevoix and Cavelier, through the Luxembourg Memoir and the accounts of Le Petit, Penicaut and Dumont, the modern-day researcher can receive a fairly round picture, with Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz providing us with most detailed, best researched and seemingly less biased accounts as opposed to some of his peers.

The Natchez of that time (the early and mid 18th century) lived in a complex of nine towns/villages, with their ruler residing in the Grand Village, according to every reporting French chronicle. He was called Great Sun, claiming a direct link to his namesake, the actual sun that rose every dawn in the sky. “… He knows nothing on earth more dignified than himself…” says Le Petit; “ … he carries the title of brother of the sun…”

From his house that stood atop of the mound and whose front door was facing the east, the great ruler was greeting his awakening “elder brother”; he “… salutes him with many howlings as soon as he appears above the horizon… then he gives orders to light his calumet and makes offering of the first three puffs… afterwards raising his hands above his head, and turning from the east to the west, he shows him

The rest of the villages, according to Penicaut this time, eight in their number, were governed by Great Sun’s relatives and family members, carrying the title of “little suns.” Whenever sent for, a tribute in goods would be paid to the great sovereign, whose rule over all the rest of the towns and villages was absolute and unchallenged. On that again, every French source seemed to agree.

“… his house on top of the two-terraced mound was so spacious it could host four thousand people and no one dares to visit him there without a correct invitation..” (Penicaut).

Even when invited, no man would dare to come closer than four paces to the sacred person of their ruler when bidden to speak, and not before saluting to him in specific cries of politeness (according to both Penicaut and Le Petit). When bidden to leave, people did so in a backwards step, not disrespecting their ruler by turning their backs on him, uttering more cries of politeness.

Only his principle wife was allowed to near his person with no reservations. Curiously, this same seemingly privileged woman was typically coming from a humble background. No highest nobility according to custom could marry their equals in status. The custom was most firm on that. Every noble, even the Great Sun himself, has to marry “downwards,” and as the succession was to come from the women, the Great Sun’s children were not only out of chance to inherit their great father’s elaborately decorated seat of power but were actually forced to move downwards on the social ladder in general, turning into a lower nobility called “honorables.”

Which was not the case with the females of the Sun Family and their progeny. A woman of such royal house was also expected to marry a man from a simpler background; however, her marriage was reported to be a choice, with possibilities of sending her husband back home in disgrace if he displeased her, according to Le Petit. Moreover, the children of such lady would inherit her highest status, just like the children of her powerful brother-ruler would inherit the status of their lowly mother.

And so one can guess even without reading on who would become the next Great Sun. Yes, the son of the current ruler’s sister or the closest female relative.

Penicaut claimed to pester the Natchez people he was friendly with with questioning on this particular arrangement. The answer he received was definite and firm – “… nobility can come only from the woman, because the woman to whom children belong is more certain than the man…”

Or, according to Dumont, who presented other people with the same question “… if it should happen that this Stinkard woman [the nickname to the lowest of the classes Dumont and some other French used as would be explained below] should by chance yield herself to a Stinkard man and the child that arose from this intercourse came to command us, it would follow that we would be governed by a Stinkard, which would not be in order… On the other hand, whether female Sun has children by her husband or any other person whatever, it matters little to us, they are always Suns on the side of their mother, a fact which is most certain, since womb can not lie…”

A practical attitude. With no DNA tests available who was to say that the man’s sons were actually his. Even Great Sun himself could not be that certain of his wives, could he?

This same chosen sister of the great ruler was reported (by Charlevoix) to wield quite an influence and power, even though in general she was expected not to meddle in politics. Great respects were paid to her, and her ability to deliver death sentence on the subject that discard her was equal to her powerful and omnipotent brother. Also, according to Charlevoix, the Sun Family females, while expected to take lesser men for husbands but free to discard them if such was their will, were also free to take lovers, husband or not. This privilege, he claimed, belonged to the Sun Family alone.

Nowhere near the status of the sacred royalty, the honorables who served the city and its ruler in various administrative capacities, enjoyed enough privileges as well. The Great Sun or the “lesser suns” who ran smaller towns and villages for him, were expected to appoint their advisers and other officials – two war chiefs, two masters of the ceremony, two officials to regulate what was done in treaties of peace and war, an additional official managing the conduct of the public works, and four honorables responsible for public ceremonies and feasts. Such people wielded plenty of power and influence and their lives seemed to be well set. War chieftainships and most secondary offices were open the second rank of nobles.

After the “honorables” came “considerates” who might have been the equivalent to the middle class – lesser officials and overseers, tribute collectors, traders and maybe some craftsmen as well.

The last ones on the ladder of social honors stood, according to all French sources, the common people, the bulk of the population – farmers, construction workers and such. Those were called “miche miche quipy” which could be translated as “those who smell differently.” A polite way to hint at something? Some French, Dumont among them, proceeded to translate the term into French as “stinkards.” To rise from such status one has to perform “… actions of valor which may raise them to the dignity of Honored men …” (Dumont). Even though, judging by the combined French records, the custom of the mandatory intermarriage between the classes seemed to keep constant movement or exchange of blood and statuses on the long term generational level.

As Dumont has explained in his memoirs, if there was only one Quachilli-Tamailli (Female Sun) and she bore a boy and a girl, the boy would then become Quachilli-Liquip (Great Sun) and lawfully established rule, but his own children would be considered nothing but honorables – “… the children of those become simply Honored, and the children of these last fall back into ranks of Stinkards … ”

On the other hand, the female children of the girl born by this same first Quachilli-Tamailli, while not becoming actual rulers, would keep their status of the highest nobility along their female born line from generation to generation.

It seemed to be an interesting custom that might have been developed to keep people from intermarrying among the extended families. And if so, it may point out that the Natchez People had relatively small population and that maybe it was not so among their direct ancestors, the legendary Mississippians who lived in evidently large communities and cities and so had larger pool of spouses from among their own classes to choose.

Du Pratz, who gives us most interesting, detailed and seemingly less biased by his own upbringing account of the Natchez People and their traditions, cultural values, customs and their everyday lives, says that even the way of talking among the commonplace miche-miche-quipy, or what the French unanimously called stinkards, was different. The language of the nobility was “… soft, solemn, and very rich …” According to his chronicles, the term miche-miche-quipy was used freely but never in front of the common people themselves, probably out of politeness and because “… it would put them in a very bad humor …”

He reinforces the claim of Dumont regarding the gradually degrading status of the suns through their male line and the continuation of the nobility in females.

He also adds that another reason for the custom of “marrying down” in the ruling nobility might have been the fact that the members of the Sun Family were sacred and could not be harmed or inflicted violent death upon. Which collided with another firm custom.

Upon Great Sun’s death, his wives, at least a fair representation of those, were expected to follow their master into the afterlife, to keep him company there and to be of use to him as they were in the earthly life, along with a few chosen servants. Which could have presented a contradiction if the Sun was married to a woman of his own sun status. Being a Sun herself, such wife could not be put to death, and so the great ruler would have to go on in his afterlife without a company of his dear one or ones. Which could not be allowed to happen. Apparently, having wives from among lower classes solved this particular dilemma.

The subject of marriage customs among lower classes, actual wedding ceremonies and other festivities will be expanded in the next article.

Comments

No Comments to “The Dubious Privilege of Being a Son of the Great Sun”