In Mesoamerica of 16th century the dilemma was simple.

In Mesoamerica of 16th century the dilemma was simple.

Was it better to bath once a day or once a month?

The state policy of reorganized by the Spanish authorities Tenochtitlan stated that once a month was more than enough. Any more frequent visits to temazcalli – Mesoamerican traditional steam bath – was illegal and open to a government punishment of “one hundred lashes and to be bound for two hours on the marketplace”. Not a pleasant experience. But then to go about stinking, sweat-covered and lice-ridden was not a much better option. Mesoamerica was not a happy place in the post-Columbian times.

However, only a century earlier, in pre-contact Mexico, the things were quite different. All over Mexican Valley and its surroundings, Highlands and Lowlands alike, no settlement, however small, would exist without more than a few traditional bath-houses. How could they? After all, those bath-houses combined pleasure with health. A happy combination.

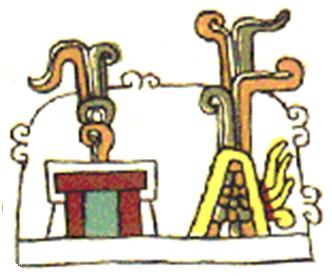

The word temazcalli means just that – temaz-bath, calli-house. The old goddess Temazcalteci, the grandmother of the baths, was watching over the medicine practice in general, worshipped by healers, surgeons and midwives. With steam baths being the integral part of a healing process, the goddess’s image would adore many respectable bath-houses.

Mesoamericans of all ages and sexes would enter the small, mushroom-like construction, squeezing in through a low doorway into the dark world of heat and humidity, shaking off the worries of the day, exchanging the agitation of the gushing outside life for a chance to sprawl and relax, to have a good conversation or simply to connect with one’s inner self.

The bath-houses were usually built to resemble a shape of a woman’s womb, so, after sweating profoundly in the unbearable heat, after scrubbing one’s body with bunch of twigs or grass, the bather would emerge back into the world cleansed, at peace and as though reborn.

The system worked simply. A large fire was maintained, blazing next to one of the walls – usually the wall facing the east, in a deference to the sunrise – until it was red-hot. Then the bath operator would enter, pouring buckets of water over the glowing bricks, filling the crammed space with so much steam, the bathers would be hardly able to see themselves.

The medical benefits of such a pastime were amazing. From various skin and liver deceases to blood circulation, rheumatism, arthritis, muscular pains and colds, temazcalli would help with any of those and more, while maintaining Mesoamerica clean and sweet-smelling.

An excerpt from “The Warrior’s Way”

A new outburst of steam clouded the air as the slave came in, in order to splash more water upon the glowing red-hot wall. Atolli stretched, then raised his hand lazily, reaching for a bunch of twigs.

“I could stay here for all eternity,” he muttered, sinking back onto the stone bench padded with grass. “I hope we stay in Azcapotzalco for another day. Fancy enjoying the benefits of the civilized living for a little longer.”

In the thick mist of the swirling fumes he could hear his brother growling.

“I’ll switch with you anytime. You stay here to slumber and sweat and I’ll go against the Chalcoans.”

Atolli laughed. “Relax, young hothead. There will be more campaigns. We won’t finish the Chalcoans in one miserable raid.” He began scrubbing the sweat off his shoulders using the twigs. “I wonder how our Aztec reinforcements will fare in the sands of the east. I bet they haven’t seen anything like that.”

“How was that altepetl of theirs? How it really was?”

“I told you yesterday.”

“You said nothing yesterday. Mother kept getting all agitated and you kept being so very careful. ‘Yes, a nice city. Yes, they dug some canals.’ Come on! I don’t believe you did nothing but train warriors.”

“All right, we did some things. I told you about the whores with the blackened teeth, didn’t I?”

“What did you do the next night?”

“Nothing. We’d had enough of their marketplace by that time.”

“So you didn’t get to sample any of the local girls at all?”

“No. No doing cihuas. I will make sure to rectify that matter when I bring their warriors back.”

“Why would you bring their warriors back? Someone else can do that. You are too good to be sent on such errands.”

“I promised their ruler.”

He could hear Tecuani sitting upright. “Why?”

“It’s a long story. Maybe I’ll tell you when I’m back from this raid.”

The slender, slightly foreign-looking face swam into his view as the young man leaned forward, peering at Atolli through the dispersing mist.

“I have a bad feeling about this one,” the youth murmured, a frown not sitting well with the fine-looking gentle futures. He remembered Tecuani as a boy, unruly and full of mischief.

“What?”

The young man shrugged, his eyes suddenly guarded.

“Bad feeling about what?”

“This raid. Back in the gardens, when we were messing around, I suddenly… I don’t know. It felt bad and ominous. I had a feeling we will never be the same after this campaign.”

“It always feels like that before raids. It’s nothing. You get used to it.”

“I’ve been to wars!” cried the youth hotly. “I did a summer of shield bearing and I’ve been a warrior for more than a few moons. I know how it feels before, after and in the middle of the raid. I’m not a calmecac pupil anymore!”

Atolli sat up. “Calm down. I know all about you, oh Great Warrior.” He slapped the youth’s thigh. “Relax and get over your bad feelings. You feel that way because you can’t go with us. But Father is right. They may send for reinforcements, if you think about it. So just make sure you are available and we will yet get to fight together in the very near future.” He lay back. “Now let me enjoy my bath.”

…