Upon the great mounds of Cahokia and the rest of the great Mississippian cities, life was reported to be significantly different than among the dwellers of the countryside and the simpler towns and neighborhoods.

As mentioned in the previous article, the lower class people did not practice polygamy, or did so sparingly, according to their ability to support an extended family.

Even the mortuary rites for nobles did not stray from the regular mourning ceremonies through which the deceased would be carried to his or her grave arrayed in their most beautiful dress, ornamented and painted, with customary amount of provisions and utensils to ease the impending journey. Through the first month, the relatives would come to their deceased grave’s twice a day, at dawn and at dusk, the nearest relatives doing this for three months, while cutting their hair in the sign of grief and abstaining from painting their bodies or participating in town’s festivities.

However, it all changed when the leading member of the Sun family was the one to embark upon his or her afterlife journey. The early 18th century French sources are gushing with the descriptions of the mortuary rites when it came to the great chiefs among the Natchez, and the archaeologists and anthropologists have enough proof to believe that such customs were practiced among the original Mississippians centuries back, when the great mounds were built among the vibrant urban centers and communities.

When a member of the Sun Family died, Quachil Liquip/Great Sun himself, his brother carrying the title of Tattooed Serpent, or his full sister Quachilli Tamailli/Female Sun, the funeral rites were special, lasting for more than four days and costing in plenty of luxury items and several human lives.

First of all, the principle spouse, the favorite wife of the deceased ruler or the husband of the deceased Female Sun, would be expected to accompany their noble spouse in his or her afterlife journey.

According to Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz‘s testimony

“… when any member of the suns, died, whether male or female, the spouse, several friends and followers, and slaves would be strangled to death sacrificially so that they could cross to the spirit world with the sun. Dying for this cause was considered to be a joyous opportunity…”

With Iberville’s account backing this statement:

“…upon the death of the last chief, two women, three men, and three children were put to death… strangled with bowstring… these wretched victims deeming themselves greatly honored to accompany their chief by a violent death.”

Du Pratz goes into great details on the funeral rites that followed the death of Tattooed Serpent he was privileged to witness and even allowed to participate, if only partly.

“He [Ouitiqui-Tlatagoup Tattooed Serpent] was on his bed of state, dressed in his finest clothing, his face painted with vermilion, moccasined as if to go on a journey, and wearing his crown of white feathers mingled with red. His arms had been tied to his bed (bow, quiver of arrows, warclub).Around the bed were all the calumets of piece which he had received during his life, and nearby had been planted a large pole, peeled and painted red, from which hunge a chain of reddened cane splints, composed of 46 links of rings, to indicate the number of enemies he killed…

The company in the cabin was composed of the favorite wife, of a second wife whom he kept in another village, to visit when his favorite wife was pregnant, his chancellor, his doctor, his head servant, his pipe bearer, and some old women, all of whom were going to be strangled at his burial. To the number of the victims there joined herself a Noble Woman, whom the friendship that she had with the Tattooed-serpent led to join him in the country of spirits.

These things filling us with sadness, the favorite wife, who perceived it, rose from her place, came to us with a smiling air, and spike to us in these terms: “French chiefs and nobles, I see that you regret my husband’s death very much. It is true that his death is very grievous… his ears were always full of the words of his people and yours… he carried both in his heart… But what does it matter? He is in the country of the spirits, and in two days I will go to join him and will tell him that I have seen your hearts shake at the sight of his dead body. Do not grieve. We will be friends for a much longer time in the country of the spirits than in this, because one does not die there again. It has always fine weather, one is never hungry, because nothing is wanting to live better than in this country. Men do not make war there anymore, because they make only one nation. I’m going and I leave my children without any father and mother. When you see them, remember that you have loved the father and that you ought not to repulse the children of the one who was always been the true friend of yours.” After this speech she went back to her place…”

As stated above, when Quachilli Tamailli/Female Sun died, her commonplace husband as well as her favorite servants and retainers were expected to join and be joyous about it.

According to both Andre Penicaut and Charlevoix, the husband was to be hastened to join right away, strangled soon after the noble woman let out her last breath. However, when it came to other retainers, the custom of four day mourning was to be followed to the letter.

“…The great house she lived at would be cleared of all it contained and a sort of a triumphant platform erected instead. Twelve infants were strangled by the order of the eldest daughter of the deceased female dignitary, to be placed around the two dead bodies. Simultaneously 14 wooden platforms would be prepared in the public square, ornamented with branches and painted mats. On each such scaffold a man or a woman who were to accompany the deceased would place themselves, surrounded by the nearest relatives, themselves having prepared the cord with which they would be strangled. It was a great honor to be chosen and some people applied ten years in advance to obtain such honor, required to make the cords that would eventually strangle them themselves…”

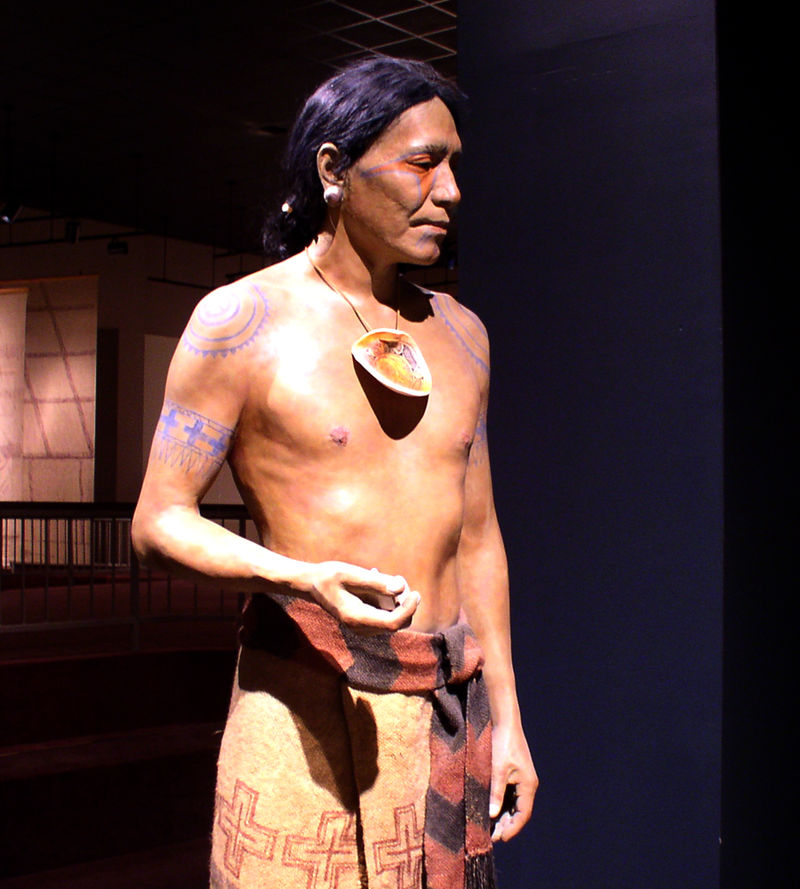

Through the following days, the victims in however amount they volunteered would spend their time on their special platforms, dressed in finest of clothing, decorated with the best of the jewelry and ornaments that their family and sometimes their entire community gather for them, including a large shell that had a ceremonial value, signifying their special status.

Greatly respected, assigned with five servants (Penicaut), their faces painted red and red ribbons tied to one of their legs, every member of the community would strive to be first to feast them and do any of their wishes. Every now and then, a death cry would be uttered, upon which those people would descend their platforms and unite in the middle of the square to engage in ritual dances in front of the temple or the house of the deceased. In the more ancient times, the temple and the palace in which the rulers of the Mississippian cities and towns dwelled were probably adjacent to each other.

After four days of such reoccurring rituals, mourning and feasting, “the march of the dead bodies” would begin, according to both Charlevoix and Penicaut. Several dead infants, strangled by their parents who had volunteered to do that (the families of the sacrificed infants were to be elevated to the ranks of the nobility with hereditary rights), were brought from their homes, carried by their fathers who were to join the procession as the others sacrificial offerings walked with their closest of relatives amidst ritual dancing and drumming to the house of the deceased ruler. If it was the father of the family who was to die, his eldest son would be the one walking with him, bearing his father’s warclub in his right arm and the cord for strangling under his arm; if to was the mother of the family then it would be the eldest daughter walking beside her, carrying the cord.

Du Pratz’s story is more detailed.

“…A few moments later the grand master of ceremonies appeared at the door of the dead man’s house with the ornaments which were proper to his rank and which I have described. He uttered two words and the people in the cabin came out… Each of the prospected victims was accompanied by eight male relations, who were going to put him to death. One bore the war club raised as if to strike, and often he seemed to do so, another carried the mat on which to seat him, a third carried the cord for strangling him, another the skin, the fifth a dish in which were five or six balls of pounded tobacco to make him swallow in order to stupefy him. Another bore a little earthen bottle holding about a pint, in order to make him drink some mouthfuls of water in order to swallow the pellets more easily. Two others followed to aid in drawing the cord each side.

Very small number of men suffices ti strangle a person, but since this action withdraws them from the rank of Stinkards, puts them in the class of Honored man, and thus exempts them from dying with the Sun, many more would present themselves if the number were not fixed to eight persons only. All these person that I have described walk in this order, two by two, after the relations. The victims have their hair daubed with red and in the hand the shell of a river mussel which is about 7 inches long by 3 or 4 broad. By that they are distinguished from their followers, who on those days have red feathers in their hair. The day of the death they have their hands reddened, as being prepared to give death.”

The dead infants would be placed on both sides of the entrance into the deceased noble’s house, while the adult victims take their places alongside them. The rest of the mourning crowd would arrange itself all around, dressed in their best clothes and with their hair cut in an additional sign of mourning. Those who are destined to die would dance to the singing of the mourning crowd.

When the body of the deceased Sun or Female Sun has been carried out by four bearers, the march would recommenced once again, while the house of the deceased ruler was set on fire.

“… The fathers of the sacrificed children carry their offerings, marching in front, four paces from each other. Every ten paces they lose their step and let their burdens fall, for the carriers to pass above them and their offerings, them reassume their places in the march. Upon reaching the temple the sacred body is carried inside, while the victims are made to kneel on the ground before the entrance, with two attendants each, one to sit on his knees the other to secure his hands behind his back, while a cord being placed around their necks and deerskin covers their heads. The victims swallow three pills of tobacco with a draught of water to help it along, which make them loose their conscious. The relatives of the deceased dignitary arrange themselves at their sides and sing, drawing end of each cord until the victims are strangle. Then all of them are buried in the same pit along with the infants…”

Archeology suggests that such customs were practiced widely in the earlier times in urban centers like Cahokia and other Mississippian cities, with maybe even a greater number of wives and retainers expected to follow their Great Sun or Female Sun into their new beginning.