His name Chimalpopoca meant Smoking Shield (Chimal(li)-shield, popoca-smoke/smoking), and he came to succeed his father, Huitzilihuitl, in the year of 1418 or Four Rabbit-Nahui Tochtli.

Some sources claim different dates, varying from 1414 to 1424, but most agree on 1417-18.

In the Codex Mendoza, Chimalpopoca is depicted in a typical way of Tenochtitlan’s rulers: sitting on a reed mat, petatl, wearing a headband, xiuhuitzolli, and carrying his role of a tlatoani-revered speaker with a speech scroll coming out of his mouth. The depiction of his name is added in the form of a Mexica shield with blue rim and seven feather down balls, with curls of smoke surrounding it.

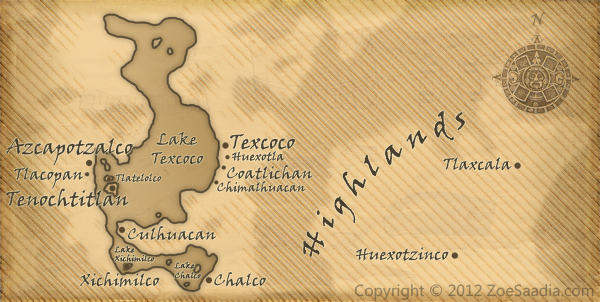

Being the son of the Second Mexica Tlatoani and his Tepanec Chief Wife, the daughter of the mighty Tepanec Emperor Tezozomoc, who by this time ruled all the lands around Texcoco Lake and the Mexican Valley, Chimalpopoca enjoyed Azcapotzalco’s continues favor, and so did Tenochtitlan alongside with him. The tribute remained greatly reduced, and the revenues from the newly acquired Acolhua provinces, including Texcoco itself, which the Mexicas received probably as a prize for their active participation in the Acolhua-Tepanec War, added greatly to Tenochtitlan’s well being.

The city continued to prosper, the buildings being further rebuilt or extended. The markets filled with luxuries along with plenty of other necessities, offering cotton clothes and precious stones, something even in Huitzilihuitl’s times was not readily available.

The first construction to carry fresh water to Tenochtitlan was finally commenced, not an overly impressive structure made out of clay and limestone, breaking down too often for anyone’s liking. Still it was better than no aqueduct at all. The water on the eastern shore of the island was brackish, good for washing but not consuming. Only the western side of the island offered readily available fresh water, and it was not as sweet tasting as the water of the mainland. Tenochtitlan people grew picky about what they were expected to consumed.

Chimalpopoca’s reign was relatively short, lasting only ten years, his military activities mainly inherited – Tenochtitlan’s participation in the Tepanec-Acolhua War, as much as the long-years’ hostilities against altepetl of Chalco, located to the south of Lake Texcoco, on the shores of Lake Chalco. Codex Mendoza lists Chalco among Chimalpopoca’s conquests, but so it does when dealing with the military efforts of his father, Huitzilihuitl, or his uncle-successor Itzcoatl. Which might indicate the long-standing hostility and raids, rather than an ultimate conquest.

Chimalpopoca died in 1427 or Thirteen Reed-Matlactli Ei Acatl and his death was not as natural as this of his predecessors. The glyph attached to his year of death in the Codex Mendoza depicts him still sitting on a mat, wearing the royal headband; yet there is no speech scroll coming out of his mouth, and his pose is slopping, eyes closed. Some sources argue about his time of death being as early as 1424 or as late as 1432.

The upheavals in Azcapotzalco’s royal house sent huge waves of unrest throughout the entire Tepanec empire, hitting Tenochtitlan’s shores with a great strength. Tezozomoc, the man who had ruled the Mexican Valley with a stony fist for quite a few decades died in 1426, leaving two dominant heirs among multitude of eligible sons.

Tayauh, or Tayatzin as most of the records tend to add the honorific ‘tzin’ to this man’s name, was the son the dying emperor named for a successor, but his brother Maxtla thought he would do better occupying Azcapotzalco’s throne.

Chimalpopoca, still a young man of barely twenty, acted unwisely by supporting the legitimate heir vocally, openly, with great zeal. It is said that both his half-uncle Itzcoatl, his Head Adviser at this time, and his half-brother Tlacaelel, the Chief Warlord, advocated Tenochtitlan’s neutrality in this matter, advising to leave the Tepanec heirs sort their differences between themselves. However young and probably impressionable Chimalpopoca did not heed his wise supporters’ advice. Tayatzin was a lawful new Tepanec Ruler and that was that. Tenochtitlan would side with this good man, would benefit from its continued support in the long run.

A good strategy, maybe, but for the discontent Maxtla resorting to less lawful means. Only a few moons into his reign, Tayatzin died, by poison applied by his brother Maxtla, or so many have assumed. Tenochtitlan found itself facing hostile Tepanec Capital led by the man Chimalpopoca was heard declaring openly against on more than a few occasions. Not the best of situations, as the Mexica Island was still no match for the powerful Azcapotzalco, rich with tribute and teeming with warriors forces.

What’s more, having discovered the delightful ease with which one could get rid oneself of his rivals with no intricate politics involved, Maxtla didn’t even try to make it look legal. Next to die was the ruler of Tlatelolco, Tenochtitlan’s sister-city located on a neighboring island. Then Nezahualcoyotl, the exiled Acolhua heir whom Tezozomoc allowed to live in Tenochtitlan and even in the former Acolhua Capital through the recent years, was forced to flee back to the Highlands, after a failed attempt on his life.

Chimalpopoca found himself isolated, threatened openly. And so did Tenochtitlan, unpopular now in the new royal house of Azcapotzalco.

Itzcoatl and Tlacaelel began preparing for war. Tlacaelel, the Chief Warlord was reported to be “… seen everywhere around the city, fortifying it against the possibility of a siege, strengthening people’s spirits as well…”. The island’s location was offering an advantage for a change. All the Mexica Capital needed to do was to block the causeway leading to the mainland, and make sure enough war canoes patrolled Tenochtitlan’s waters.

And then, Chimalpopoca died. Various sources disagree on the matter. Some said Maxtla has had him killed by sending assassins into Tenochtitlan’s palace. Some said he had lured the young ruler to Azcapotzalco under the pretext of an imperial feast, then took him prisoner and executed. Given the political climate of these times, the first version makes more sense.

Additional hunches pointing the accusing finger at Iztcoatl, of all people, Chimalpopoca’s Head Adviser and the man who was destined to become the next Tlatoani; the man who had the necessarily amount of royal blood, even if inherited from his distinguished father only, and no lack of other great qualifications, a hardened warrior and politician who had seen more than forty decades of life. At such time, facing the most serious crisis, about to engage in the largest military confrontation since its creation, Tenochtitlan could certainly do better with a tough leader of great clout, experience and determination. So there are scholars who suspect Itzcoatl at having his own nephew killed, the only person with a clear motive.

An excerpt from “Currents of War”, The Rise of the Aztecs Series, book #4.

Iztac felt her heart missing a beat.

“Oh, the Tepanecs have no honor at all!”

“No, they have none. Apparently, they think many of the cities and altepetls should change their rulers along with their policies.” The thickset man shrugged. “I shall double the amount of warriors guarding the Palace.”

This time Chimal jumped to his feet, unable to remain seated anymore. “They would never dare!” he cried out. “It would make the war inevitable, and they would never succeed in removing a lawful ruler of an independent altepetl, never. We are not a village!”

Itzcoatl shrugged once again. “Maxtla has no honor. He can try anything, and I don’t want to see him succeeding, even if it won’t achieve the results he might wish to achieve. Tlacateotl, the ruler of Tlatelolco, was also a lawful ruler of an independent city. Nezahualcoyotl is also not an outlaw for them to try to hunt him down the way the despicable Tepanec tried. Tayatzin was a lawfully appointed successor to the Tepanec throne, but he is dead now, and no one dares to ask questions. I don’t want it happening here in Tenochtitlan. I don’t want to see you dead, Nephew, even if your death would not make Tenochtitlan into a tributary of the Tepanec Empire.”

Not daring to breathe, Iztac listened, her heart beating fast. Oh, no, they would never dare. Never! And yet, Itzcoatl might be right. Dirty Maxtla had dared to do many things no one assumed he would do. What was there to stop him from trying to murder Chimal, whom he hated openly, whose delegation he had just refused to receive? Oh, gods!

She watched the impartial face, a stone mask once again. Did this man have Chimal’s interests in his heart, after all? Were her suspicions, her unexplained dislike of this man, wrong and unfounded?

“I appreciate your concern for my safety, oh Honorable Uncle,” she heard Chimal saying, his voice warm and heartfelt. “But I would give my life away gladly if I were required to do so for the benefit of Tenochtitlan.”

“Yes, and I believe you, Nephew. Yet, my mission is to ensure your safety for the greater benefit of Tenochtitlan.” But again, the man’s eyes flickered darkly, making Iztac shiver. He knew something Chimal did not, she realized suddenly. Something ominous and dark. Something that would scare her beyond any reason.

She shut her eyes, wishing the ominous feeling to go away. It was all her imagination. Recently, she’d had too many things to worry about, too much danger to cope with. People she loved were in trouble, all of them – Coyotl, the Highlander, and now Chimal. No, she should calm her nerves and should not let the stupid sensation of knowing the future ruin her life. She would not be of help to any of them if she turned into a quivering shouter of doom.

No, she decided. Today she would not worry, and she’d do nothing but spend a quiet day with Citlalli, her daughter, the way she sometimes liked to do. They would draw pictures and chat and laugh, and they would gorge on sweetmeats, too.

She opened her eyes in time to see Tlacaelel coming in, tall and imposing, his paces wide, his face sunburned, his cloak creased, his whole being radiating purposeful energy, smelling of lake, campfires, and adventure.

“I beg to forgive me my neglected appearances,” he said nearing the throne, not paying attention to the slaves who hurriedly prostrated themselves. “I came as soon as I could, as soon as I heard you wished to see me, Revered Brother.”

“I’m so glad to see you back, well and unharmed!” exclaimed Chimal, jumping off his throne once again. “What happened?”

“Oh, filthy Maxtla was up to his tricks again!” Tlacaelel’s nostril’s widened as he took a deep breath. “This man is the most despicable half person that has ever been born.”

“You should be flattered, Warlord,” said Itzcoatl grimly. “He seems to be concerned mainly with rulers or would-be rulers.”

But Tlacaelel just shrugged, unperturbed. “He didn’t try to dispose of me for being me. He wanted to create a problem between Tenochtitlan and Tlacopan, so that city would be the first to join the war against us.”