In 1474, the war in the Toluca/Tollocan Valley began and almost ended with the remarkable battle through which the Tenochtitlan ruler was wounded severely, an unheard of occurrence according to most primary sources. No tlatoani of Tenochtitlan or either of its allied city-states was hurt in the middle of a battle as a simple warrior would be, not until the southwestern campaign against Tollocan and Matlatzinco.

Axayacatl, the sixth tlatoani of Tenochtitlan, was a relatively young man who have ascended the throne in his mid-twenties according to Codex Mendoza, then proceeded to prove his worth as a wise ruler and not only a competent leader and vigorous warrior in the conflict with the neighboring Tlatelolco.

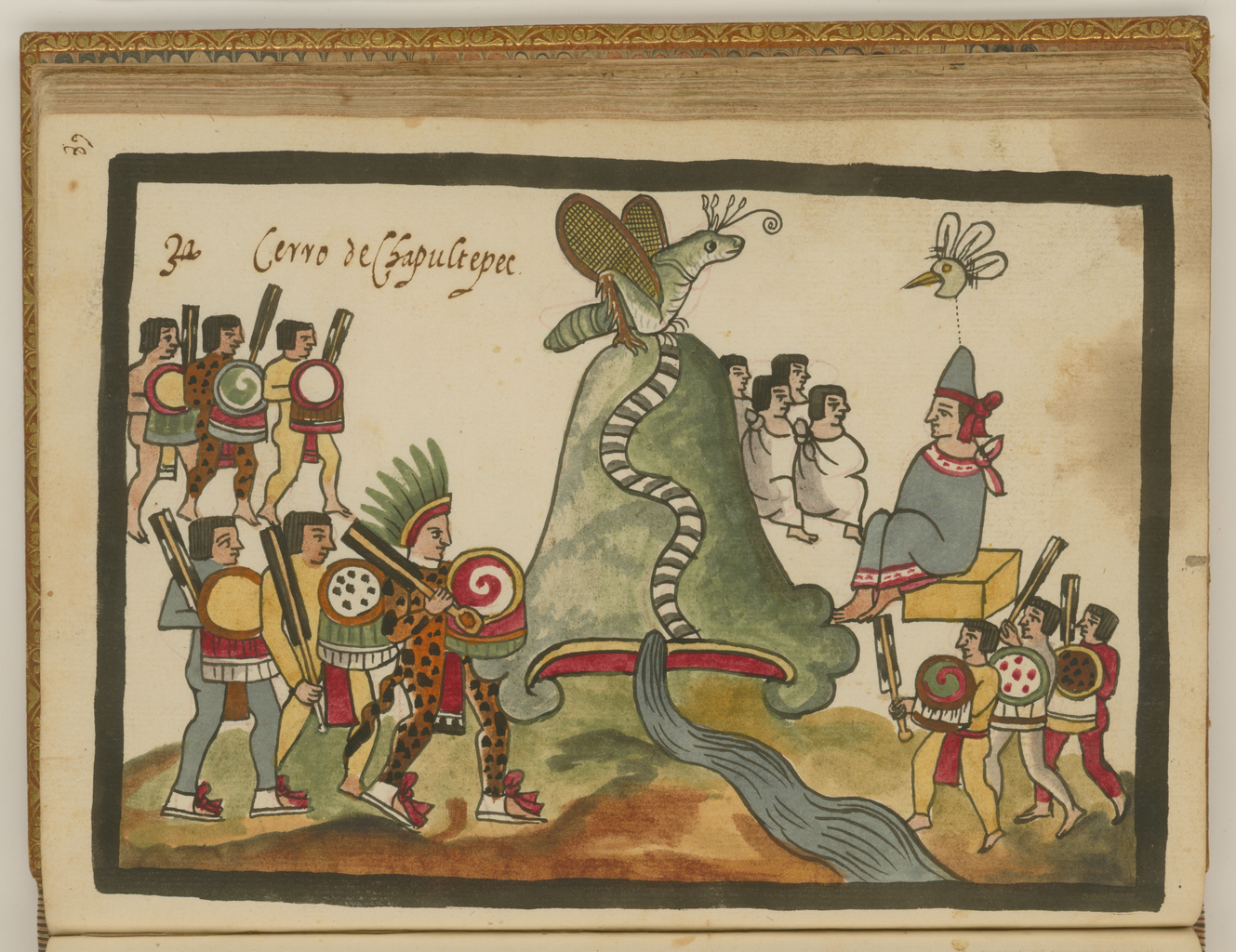

So, in 1474, he was already a proven quality, not looked down upon by Tenochtitlan’s allies and enemies alike as might have been the case in the beginning, before the conquest of Tlatelolco. Therefore, when he headed toward the southwest, following the plea of one of the local altepetls/city-states against some of its warlike neighbors (according to Diego Duran), no one was tempted to treat Tenochtitlan’s advance lightly.

Aside from Duran’s claims, other primary sources seem to disagree on the cause for the Toluca Valley’s war of 1474-75. As stated above, according to Duran, it was the ruler of the city-state Tenantzinco who came to Tenochtitlan asking for help against his immediate neighbors to the northwest, altepetls Tollocan and Matlatzinco. However, Alvarado Tezozomoc claims that it was the Tollocan ruler who came to ask for help, and thus, this altepetl, while made to pay tribute like the others, retained much of its independence that the unfortunate Matlatzinco did not (the early colonial documentation shows the Tollocan ruler of the original lineage occupying the ruling seat, paying a regular tribute, not always happy under the Mexica rule, forced to deal with perpetual discord with the new settlers, as Axayacatl took considerable tracts of land to himself and Ahuitzotl and distributed many plots between people who came with him from Tlatelolco, Tlacopan, Azcapotzalco, and Texcoco (“Aztec Imperial Strategies”, Library of Congress)).

To add to the confusion of who came to the Mexica Capital asking for help, if at all, Codex Mendoza lists plenty of the Toluca Valley’s altepetls and towns as conquered during the Matlatzinca campaign, including Tenantzinco itself, even though Duran mentions Tenantiznco as a loyal vassal who asked for help.

However, what we do know for certain is that the Triple Alliance fought in the Toluca Valley’s war together and thus ended up dividing the spoils between all three members of the alliance – Tenochtitlan, Texcoco and Tlacopan. Fernando Ixtlilxochitl mentions in passing that “… the tribute Matlatzincas paid was receive by all three kingdoms…”

Back to the first campaign in the Toluca Valley, Axayacatl, never satisfied with simple battles of two sides charging at each other, according to Duran planted a special unit of up to a thousand veteran warriors in pits or other places of concealment, camouflaged and well hidden. The plan was to lure the enemy forces into this ambush by the main body of the Mexica warriors that was expected to give a deceptively halfhearted battle, gradually retreating and thus luring the hopeful enemy into the ambush, to be attacked by the fresh forces of over thousand veterans and thus decide the battle. A well trained and well disciplined forces of the Triple Alliance were capable of executing such task.

However, it happened that the Toluca Valley forces must have thought of the same trick, as according to Duran “…while Axayacatl and his seasoned warriors and some of his bravest men stayed hidden in the ambush, covered by leaves and branches… The same trick that the Aztecs had planned, however, had also occurred to the Matlatzincas… hidden behind maguey agaves, and in the underbush…”

The strategy that resulted in a reportedly very confused beginning to the great battle that subsequently ensued, as both main fighting forces seemed to spend a whole morning fighting halfheartedly, attacking and retreating and attacking again, determined to lure the other side to their prospective sites of each ambush, unaware of each other’s aims and thus adding to the confusion.

According to Duran, the Mexica forces proved more disciplined in the end, managing to disrupt the fighting Tollocans and Matlatzinca and their northern Otomi allies, and thus finally draw their forces into the desired location, where Axayacatl was waiting impatiently with the best of his warriors, to pounce on the unsuspecting enemy and trounce them thoroughly, forcing a delightfully disorganized retreat, if not outright fleeing.

But, of course, it didn’t end there at all. The Toluca Valley’s original ambush was still there, still waiting in their designated place of concealment; maybe unaware, or maybe eager to execute the original plan at all costs. Duran claims that the Matlatzinca warriors forgot all about their original plan and fled in their earnest, with the victorious Mexica hot on their heels. However, intentionally or not, they did head for the site of the original ambush and, worse of all, Axayacatl was in their head, being actually separated from not only the main body of the Mexica warriors but from his possible personal guards as well.

According to Duran this is how the famous duel between the Mexica tlatoani and the renowned Otomi hero Tlilcuetzpalin took place (although Duran claimed that this man was one of the Matlatzinca leaders and not Otomi like the rest of the primary sources state). “… Believing that they were victorious, Axayacatl began to sound his golden drum that he carried on his back, which was played when the enemy retreated. As he went running, without waiting for his guards, the Matlatzinca officer in charge of their ambush, who was hidden behind the maguey, saw him running so carelessly, in such a hurry. He realized that the soldier was the king and felt that his own soldiers would follow him, so he suddenly jumped out from behind the agave, and drove a knife into Axayacatl’s thigh, almost to the bone, right through the king’s armor…”

The ensuing duel was reported to be vicious and bloody, with the Mexica warriors finding their tlatoani on the ground, struggling with his attackers, defending his honor despite his wounds. Duran claims that in the end, Tlilcuetzpalin, even though wounded badly as well, managed to fight his way out and escape.

According to other primary sources, the famous duel took place in different form, and sometimes even a different battle.

Francisco Clavijero is one of those who reports that Axayacatl was wounded at the battle for Xiquipilco, which took place later on to the north of Tollocan, where its lord Tlilcuetzpalin managed to bring the Mexica ruler down. According to Clavigero, Axayacatl “…received a violent wound on the thigh, and two captains of the Otomi advancing, brought him, with a few strokes more, to the ground, and would have made him prisoner, if some young Mexicas had not, when saw their king in such danger, resolutely defended his liberty and his life…”. Consequently, Xiquipilco fell and Tlilcuetzpalin was taken prisoner, brought to Tenochtitlan and sacrificed there as a custom dictated. Or so says Francisco Clavigero.

On the other hand, Fray Juan de Torquemada, a Franciscan chronicler of the early post-conquest Mexico and the author of “Monarquía Indiana”, mentions one of the Texcoco war leaders in connection to the imperial duel: “… and in the midst of the battle… Axayacatl and Tlilcuetzpalin attacked with great encouragement and struck him on the thigh of which he was wounded, followed by two other Otomies to help his master, called Itzcuani and Tlamaca and charging on him cruelly, and although he did much to defend himself (Axayacatl) the opponents were very brave and they knocked him down… Captain-general of Tezcoco Quetzalmamalitzin is aware of the scene and runs to the aid of his master and with the help of many captains of valor manage to capture B’otzanga and bound to carry him in the company of his other two captains…”

According to the Acolhua annalist Fernando Ixtlilxochitl, Axayacatl was wearing special insignia that belonged to his “brave adversary Tlilcuetzpalin” ever since besting the prominent Otomi and at the open agreement of Texcoco and Tlacopan rulers, who didn’t demand to share in this part of the victory, even though the tribute seemed to be divided between all members of the Triple Alliance according to the customary ways.

Another interesting source, this one perfectly pre-contact, came through the poetry of the famous 15th century composer of songs Macuilxochitzin , a noblewoman of Tenochtitlan and one of Tlacaelel’s daughters. Her account of the famous duel through which Axayacatl was wounded in the leg so severely he was reported to limp for the rest of his life does not match later-day sources. According to her, the famous Otomi warrior was freed by Axayacatl after women came to plead for his life.

However, as mentioned above, others (Duran, Tezozomoc, Clavigero, Torquemada) have each their own version, as varying from each other as from what Macuilxochitzin have reported. Some say (Clavigero) that the Otomi leader was taken prisoner, brought to Tenochtitlan and sacrificed with plenty of honors and pomp. Others (Duran, Torquemada) claim that the man managed to fight his way out and away in the melee of the battle while the Tenochtitlan ruler was tended to, wounded beyond the ability to chase his enemy. Another primary source (Alvarado Tezozomoc) claims that the famous duel was not commenced at the battle for Tollocan at all, but took place a few years later, when the Triple Alliance’s forces came to conquer Xiquipilco.

In his native Otomi lands of the northwestern Central Mexico, B’otzanga (or Tlilcuetzpalin, as he is called in the Nahuatl-recorded sources, with both Nahuatl and Otomi names having the same meaning – Black Lizard) is still remembered and praised. Over the centuries, the Otomi who settled in the region to the north of the Toluca Valley gained reputation of fierce warriors, fighting against the Toltecs of earlier times, other groups of various Chichimec nations and, in the Triple Alliance’s times, the neighboring Purepecha/Tarascan’s advances, whose prowess as a warring power Axayacatl was yet to taste with disastrous consequences a few years later, after subduing the entire Toluca Valley and conquering the Otomi north as well.

According to the local lore, Xiquipilco, called Ndonguu or “Place of the Ancient House,” put up a worthwhile resistance and this was where “…the Great Chief B’otzanga (Black Lizard) was born and ruled, who, in command of his army of Eight Thousand Warriors, defended courageously the territory and the freedom of our people… who fought hand in hand with the invincible Axayacatl and defeated him in the Batha Nts’ojuai (known as the Plain of the Knives)…”

To this day, this national hero’s statue dominates the imposing Otomi Ceremonial Center to the north of modern-day Toluca and various songs were written about him as the centuries passed.

An excerpt from “Valley of Shadows”, The Aztec Chronicles, book #6.

Necalli dared to wipe the sweat from his eyes, still dizzy and slightly disoriented, his elation welling. Oh, but what a good stroke of luck it was, to run into the Texcocan and while dragging a captured warrior, for his veteran to see for himself.

“Come along.” The redoubtable leader was already waving him and the rest of his warriors on, heading along the incline, difficult to keep up with. “I want to get a better look.”

When they paused, Necalli welcomed the chance to rearrange his weaponry, still hopelessly messed up, clutched in one hand, not ready to fight should they get attacked. A few groups of enemy fighters tried to do that, but YaoTecuani’s followers took care of this. Their leader was too busy scanning the view spreading under their feet, the valley crawling with warriors from both sides, vibrant with colorfulness, strangely attractive despite gruesome sights if one concentrated on details. Pockets of fighting seemed to ignite all around, rolling along the trampled brownish grass. In this time of the seasons, the valley should have been brilliantly green, and it was, oh yes – until this morning. The brownish hue was not something natural, intended by the gods.

“They are still trying to retreat, the filthy pieces of human waste,” muttered the Texcocan, twisting his lips in an ugly manner. The flurry of commands sent half of their following scattering.

“Why are they doing this?” ventured Necalli, wishing to call his mentor’s attention to him and thus offer his services. It was not an honorable thing to do, to enjoy this unexpected respite, was it? And he was enjoying it, he was! He gripped his sword tighter.

“Trying to pull us into the trap of their own.” The Texcocan shielded his eyes, then strolled closer to the other side of the incline, scanning it with his eyes narrowed into mere slits. “Just like we are. Resourceful people. Maybe their side peace offering was another ruse. To put us off guard or something.”

Necalli tried to think it all through, the unwelcome twinge of worry for Miztli’s brother returning. “Wish we could—”

“We’ll have to change our tactics. Or your emperor will fall asleep out there in his snugly padded pits of the maguey fields.” His stride forceful, the man strolled back toward the remnants of his following, sending more of his men rushing down and back into the melee. “Come along.”

But just as they began rushing down the hill themselves, the man halted abruptly, shielding his eyes once again. “Speaking of your emperor…” His palm was rock-hard, gripping Necalli’s shoulder, forcing him to look to their right, where the fighting was progressing more calmly and orderly, with less unorganized pockets of clashing. “Your friend. See? Down there? To the right of that standard-bearer. Intercept him. He is clearly looking for some of us, and on behalf of your emperor I bet. Bring him to me with no delay. Go!”

As though he needed this additional command. His excitement welling again, Necalli rushed down the slippery grass, ready to return to the battle, his strength recovered, the thought of the captive he took – all by himself, with no help from his veteran at all! – giving his legs more power, making them bounce off as though a pair of wings was attached to those. It’d be good to see Miztli, to fight together again. It was a lonely fighting until now, the only drawback, like back in Maxtlacan until that young Acolhua noble befriended him.

“Necalli!”

Poor Axayacatl, getting wounded at his thigh! I myself once had a big 3 cm deep wound at my left thigh which made me limp for a month so I can relate.

Oh absolutely, those are not the best places to get nasty wounds. He was reported to limp for the rest of his life 🙁